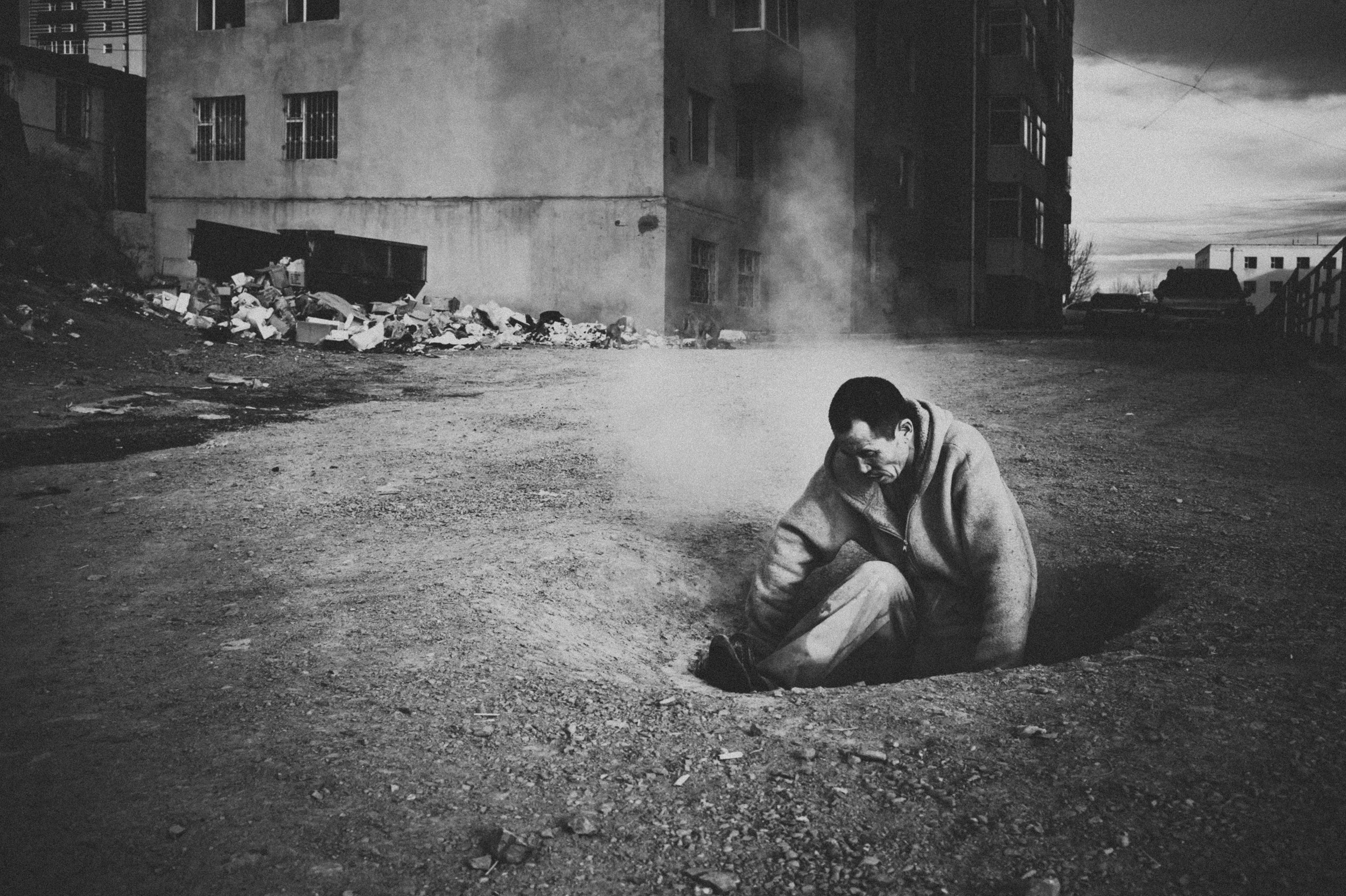

Mongolia is a land of contrasts. There is the steppe, shimmering white and seemingly endless. Where nomads graze sheep and cows in ever-changing places of the plentiful fields. And then there is Ulan Bataar, the capital, where a safe place to sleep is by no means a given. At dusk, the homeless heave aside the manhole covers, squeeze themselves through narrow pipes and huddle against the conduit system to survive the cold winter nights. Only the daylight reveals their faces, raddled from deprivation and vodka. Better off are the janitors who have settled down under the staircases in some of the apartment buildings. Flowery bed sheets and ticking clocks provide a touch of cosiness. The dwellers of the yurts, whose round tents mark the urban fringes, are able to walk upright. More and more nomads mix with them; some have lost their livestock, and with it their basis of existence, in one of the frosty winters; others simply try their luck in the city. It is said that today hundreds of thousands of Mongolians live in neighbourhoods consisting solely of yurts. They heat with carbon because they are not connected to the district’s heating grid, contributing for their part to the air pollution in one of the coldest capital cities in the world. Nearly one out of three Mongolians live below the poverty line, dreaming of a better life without hunger and cold; where worries don’t consist of the everyday struggle to survive and where a place of employment secures a share of the country’s prosperity. Only then perhaps would the yearning for the communist days fade. Ulan Bataar shows two faces; one of hardship, but also one of hope.

The centre of the metropolis is home to the winners of capitalism, to those who look favourably onto the city’s changing social fabric. Here, the vertical line dominates over the horizontal with new apartments and companies pooping up like mushrooms. Skyscrapers are blocking each other’s views onto the luxury cars that travel along the broad boulevards. In these areas of the city everyone has invested in something. Everyone has a project. And everyone a credit card. Mongolia ranks as one of the world’s most resource-rich countries. In a couple of years, Ulan Bataar will have changed beyond recognition. The city, already home to more than half the population, will continue growing. More skyscrapers will emerge and more open space will have to make way for luxury apartment buildings and for more large mansions with even larger underground garages and lavish parks. These social and spatial upheavals also find their reflection in the country’s culture.

Above all the youth scene seems to aspire after the West; many interesting projects have emerged in the fields of street art and design. The rapper Gee, a child of the yurts, found his luck in the colourful world of Ulan Bataar through his rap music; today only his songs tell of fearful nights and daily hardships. Mongolian life is in a state of flux and much has turned to good account. But still today life for large parts of the population means struggling on the edge of survival.

Will they be able to claim part of the benefit that the country’s future promises? Will the ‚new’ society provide a place for everyone or just a few? To what extent will tradition be replaced by modernisation? Will the increasing energy consumption that goes along with economic growth be covered in the future?

The multimedia reportage of Kostas Maros and Patrik Felber provides an unbiased view onto a changing world – and this is the reason they succeed, in an impressive and touching manner, in illustrating the contradictions of this country in transformation. Their acknow-ledgments go to the aid organisation Bayasgalant, which provided support for this reportage.